Colonial legacies and neo-colonial influences are still greatly prevalent within British Museums to this day. By specifically focusing on the stolen, or “converted”[1], artefacts of the Lamassu within the British Museum, my aim is to offer readers ways in which museums can begin dusting off their over worn blankets of perpetuance and ignorance.

Indeed, as scholar Claire Wintle correctly acknowledges, “there was no complete ‘transfer of power’ from Britain to her ex-colonies during decolonisation”[2] which is partly why “imperialism continued to infuse cultural economic and political life”[3]. This “infusion” can be vividly seen within museums who act as our cultural and historical time machines as their displays act as “microcosms”[4] of the colonial legacy.

British imperial power still dominates and controls the ways in which displays are showcased. However, with the aid of key contemporary anti-colonial scholars, there are many powerful as well as subtle ways in which we can slowly begin to decolonise British museums and, in turn, society.

Why the British Museum needs to revise their labels

One of the more discreet ways the British museum tends to perpetuate its colonial roots can be easily located within the stolen artefacts’ label. These labels that supposedly aim to ‘educate’ visitors, blatantly ignores the artefact’s rightful place of origin and how it came to be situated in the museum in the first place. In order to even start decolonising a museum founded by imperial rulers, the museum itself must admit to its problematic past and acknowledge the need to make a change.

This small yet vital step towards positive change can be done even in smaller ways such as revising artefact labels, acknowledging the museum’s role in the continuation of colonialism within the modern sphere. Humility is key.

As an example, I have chosen the sculptures of the Lamassu in which my revised label aims to address their status as former British colonial property instead of ignoring it.

In the ideal case, after their display period, the Lamassu would be returned to the Iraq museum, with hope to continue to foster a collaborative future[5].This display will aim to “celebrate…a more radical version of decolonisation to be enacted in material form”[6].

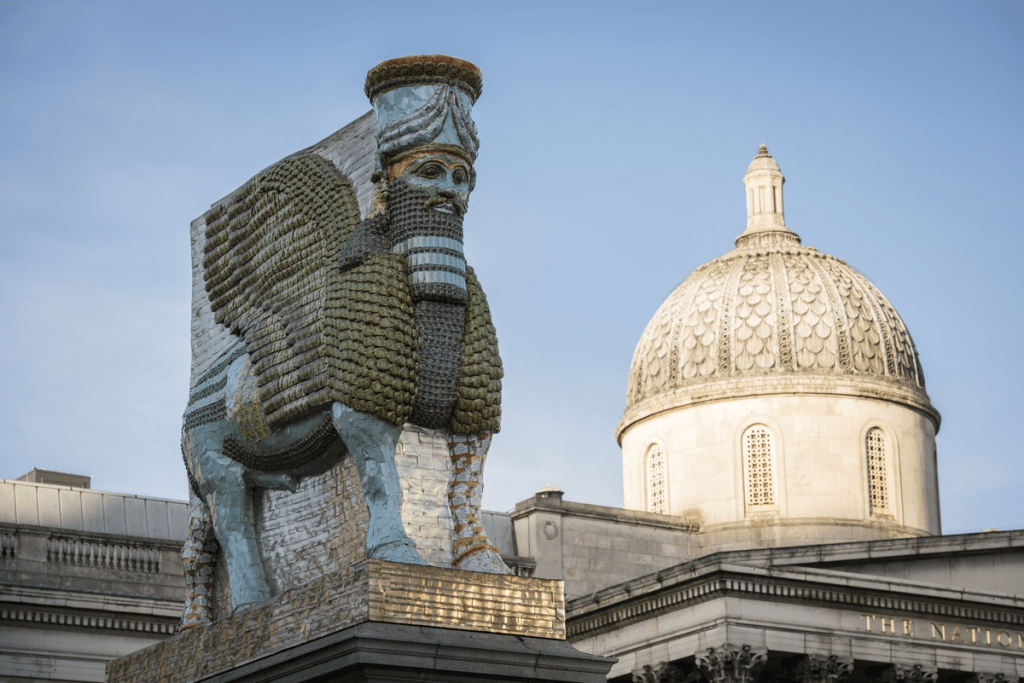

These revised labels would spread a more powerful message if the museum considered to collaborate with anti-colonial scholars and artists of our time in order to show the negative impact colonialism has on modern art and culture in the UK. For example, the Lamassu I have chosen to create a label for would educate visitors more by collaborating with someone like the anti-colonial artist, Michael Rakowitz.

My aim is to compare the original stolen Lamassu with Rakowitz’s anti-colonial statue[7] in hopes that the museum will utilise its influence, both politically and culturally, by addressing its past colonial ties and actively introducing anti-colonial concepts.

Before and after

The original label of the Lamassu statue describes it as a:

“Gypsum statue; human headed winged lion… that flanked the doorway of… the…palace of Ashurnasirpal in Nimrud”[8].

Although there is nothing factually incorrect about this description, the museum fails to acknowledge its religious, geographical and cultural origin. Most museums in Britain fail to outline these artefacts’ cultural and geographical significance, perhaps in fear of having to acknowledge Britain’s colonial past.

By focusing on this past, artefacts are no longer simply a means of educating the masses, but we are also able to bring attention to modern debates of property and decolonisation, making it hard to ignore the fact that these museum artefacts do not belong in a foreign land.

My revised label aims to address the museum’s previous ignorance and errors:

“Neo-Assyrian Lamassu Sculpture: Excavated by Sir Layard during Britain’s imperial regime from modern day Iraq and acquired by the Institute in 1851. These human-headed winged bulls protected the Assyrian king and land from dangerous forces. The Lamassu are only two of the countless Iraqi artefacts which have been ‘stolen’ and held in Western museums, alongside the 8,000 looted during the US invasion of Iraq and the countless many others destroyed by ISIS. Unlike Michael Rakowitz’s statue[9] (displayed beside the Lamassu), the Lamassu have been unable to both perform their duty of protecting the Land of Iraq as well as to be stored in an Iraqi Museum, their rightful place. These Lamassu are the centre of our new display, ‘Fighting Back the Invisible Enemy’, inspired by Rakowitz’s project The invisible enemy should not exist[10]. It symbolises the stolen past of Iraq; a hostage of the invisible enemy’s (imperialism’s) dual attempt at concealing its formidable past and its persistent yet hidden control. The British Museum is fighting back through anti-colonialist collaboration and actively returning the Lamassu after the display period is over.”

My aim is to have Rakowitz’s project[11] (or at least projected images of his project) placed next to the Lamassu statue to compare the stolen artefact with Rakowitz’s empowering statue, giving voice to Iraq’s misrepresentation and loss of culture.

In this way, the museum can be decolonised by taking the first big step of admitting it’s past dominance over former colonial artefacts as well as its current and hidden control over collaborations[12]. Through this, the museum is not only admitting its errors but also taking a solid stance against colonialism.

Michael Rakowitz and anti-colonial art

Rakowitz’s project The invisible enemy should not exist[13] is an anti-colonial and ongoing project. He describes it as an:

“intricate narrative about the artefacts stolen from the National Museum of Iraq”[14].

His aim is to recreate these stolen artefacts as “ghosts to haunt the Western museums”[15] and place “the viewer in the position of an Iraqi… [showing] how much of their history they did not have access to”[16]. Instead of these stolen and destroyed artefacts staying in the past as a taboo topic, Rakowitz is bringing the problem of Western dominance to life.

Many would argue that, as imperialism no longer exists, society should progress forward, leaving its past behind. Whilst this seems like the ideal solution, anti-colonial projects highlight imperialism’s long-lasting impact on people from ex-colonies, which cannot be ignored.

Using the idea that a “museum holds it value because it can tell you where [an objects] is from”[17], Rakowitz’s Lamassu acts directly in opposition of this idea, protesting “crime palaces”[18] and their systemisation of culture.

His use of empty date syrup cans symbolises his protest and highlights the harmful, Islamophobic stereotypes attached to Iraq. Furthermore, Rakowitz ensured the visibility of his project by placing it in front of The National Gallery, a Western institution, with outstretched wings “still performing his duty as guardian of Iraq’s past and present… unlike the Lamassu housed in The British Museum”[19].

By having the revised label outlining the original Lamassu’s position as a stolen artefact, while also including its context, the public is educated about both Assyrian history and the legacies of colonialism hidden all around them. Rakowitz’s project will strikingly contrast the original Lamassu, forcing the museum to take accountability for acting “as a device through which those involved could retain their former imperial identities”[20].

Thinking critically about traditional monumental art

To minimise bias in curating the Lamassu display, I researched other anti-colonial projects, such as Sikander’s artwork. Her recent project “Promiscuous intimacies”[21] inspired me to think critically about traditional monumental art. Sikander’s “anti-monument”[22] aims to critique patriarchal narratives whose representations of the ‘other’ (non-Western world)[23] strengthened the oppressive elements of Western imperialism.

The anti-monument’s two intertwined female bodies go in direct opposition to patriarchal values of heteronormative desires, whilst their backward glances disrupt the “national, temporal and art historical boundaries”[24]. Similarly to Rakowitz, Sikander does not conform to traditional western art, harnessing her works to protest the fixed typologies which categorise non-western views of the ‘other’.

Through the Lamassu’s revised label, the museum announces its position against colonialism’s lasting effects, which were previously utilised as “devices”[25] for imperialistic control. Although this is not a complete process, as the museum may never truly be free from its colonial past, we must acknowledge that decolonisation is not a “graceful process”[26].

Decolonisation means being prepared for humility and accountability. British museums have shied away from voicing their colonial associations for far too long and it is collaborative exhibitions which bring to light these anti-colonial views, creating a space for true healing to begin.

References:

- Devji, Faisal and Shahzia Sikander, ‘Anti-monument: Shahzia Sikander in Conversation with Faisal Devji on Public Art’, Public Culture, 36 (2024), pp. 5–16, doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-11121447.

- Michael Rakowitz: Haunting the West’, Art21 “Extended Play”, (Art 21, 2011-2023), episode 273.

- Rakowitz, Michael, The invisible enemy should not exist (Lamassu of Nineveh), 2018, 10,500 Iraqi date syrup cans, metal frame, 70-200 x 230 x 10cm.

- Rakowitz, Michael, ‘The invisible enemy should not exist’, Michael Rakowitz, n.d. <https://www.michaelrakowitz.com/the-invisible-enemy-should-not-exist> [accessed 3 January 2025].

- ‘Sculpture’, The British Museum, n.d. <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1851-0902-509#object-detail-data> [accessed 1 January 2025].

- Sikander, Shahzia, Promiscuous Intimacies, 2020, bronze sculpture, 106.7 x 61 x 45.7 cm.

- Thomas, Nicholas, Entangled Objects: The Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific, (Pacific: Harvard University Press, 1991).

- Wintle, Caire, ‘Decolonising The Museum: The Case of Imperial and Commonwealth Institutes’, Museum and Society, 11 (2013), <https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/5392605/wintle.pdf> [accessed 29 December 2024].

[1] Nicholas Thomas, Entangled Objects: The Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific, (Pacific: Harvard University Press, 1991), p. 151.

[2] Caire Wintle, ‘Decolonising The Museum: The Case of Imperial and Commonwealth Institutes’, Museum and Society, 11 (2013), pp. 185-201, <https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/5392605/wintle.pdf> [accessed 29 December 2024].

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Michael Rakowitz, The invisible enemy should not exist (Lamassu of Nineveh), 2018, 10,500 Iraqi date syrup cans, metal frame, 70-200 x 230 x 10cm.

[8] ‘Sculpture’, The British Museum, n.d. <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1851-0902-509#object-detail-data> [accessed 1 January 2025].

[9] Rakowitz, Lamassu of Nineveh, 2018.

[10] Michael Rakowitz, ‘The invisible enemy should not exist’, Michael Rakowitz, n.d. <https://www.michaelrakowitz.com/the-invisible-enemy-should-not-exist> [accessed 3 January 2025].

[11] Ibid.

[12] Wintle, ‘Decolonizing the Museum’, 2011.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] ‘Michael Rakowitz: Haunting the West’, Art21 “Extended Play”, (Art 21, 2011-2023), episode 273.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Art 21, Rakowitz, episode 273.

[19] Rakowitz, ‘The invisible enemy should not exist’.

[20] Wintle, ‘Decolonizing the Museum’, 2011.

[21] Shahzia Sikander, Promiscuous Intimacies, 2020, bronze sculpture, 106.7 x 61 x 45.7 cm.

[22] Faisal Devji and Shahzia Sikander, ‘Anti-monument: Shahzia Sikander in Conversation with Faisal Devji on Public Art’, Public Culture, 36 (2024), pp. 5–16, doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-11121447.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Wintle, ‘Decolonizing the Museum’, 2011.

[26] Ibid.

Leave a comment