Ethical stories can be seen to predate ethical theories, serving as a basis on learning how to live a moral life. Unlike ethical theories, stories teach us in a creative and autonomous way in which the reader is allowed to embody both the character and observe as a witness to the journey. Gregory claims that stories “take us both inside ourselves and outside to others… [to] teach us truths about…the human condition”[1]. The epic of Gilgamesh is the “oldest recorded… epic in the world”[2] and serves as the original quest story for the ethical, religious life[3]. Gilgamesh’s heroic quest into humanity’s “three fundamental… problems: mortality, morality and meaning”[4] allows us as readers and moral agents to undergo an ethical transformation as we travel along his journey into self-discovery.

Gilgamesh as the OG flawed protagonist

The epic of Gilgamesh epitomises an ethical story due to its wide array of themes, ranging from civilisation to the inevitability of death. Stories are vital for understanding how to live an ethical life due to their many messages, interactive story lines and morally ambiguous characters. Gilgamesh serves as an example of this, having been labelled a “heroic yet tragic figure”[5]. Because of the uncertainty of whether Gilgamesh is a hero or a “tyrant”[6], we experience his self-discovery along with him. The epic focuses on two main journeys: the quest of killing the monster Humbaba and the quest for the meaning of life. These journeys allow us to witness Gilgamesh’s growth to becoming “a good king”[7] whilst answering “humanity’s three fundamental… problems”[8].

The quest to kill Humbaba is an arguably selfish quest in which Gilgamesh hopes to attain glory and an “established… name”[9]. Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s “equal”[10] accompanies him in this journey, although unlike Gilgamesh, he does not actively dream of attaining an honourable name. In this first journey, the reader’s traditional understandings of good and evil are challenged as we are encouraged to alter our “black and white”[11] view of the world. Mitchel highlights that “the poet makes it impossible to see Humbaba as a threat”[12] as he is only doing “his duty”[13]. Here, Gilgamesh is further unmasked as less of a hero than initially presented, challenging the reader’s pre-conceived notions of what constitutes a hero. Mitchell cleverly declares Gilgamesh’s quest to kill Humbaba “the original pre-emptive attack”[14] and compares his actions to America’s invasion on Iraq. Mitchel does not praise Gilgamesh’s successful murder, but instead, uses this comparison to critique his actions as amoral. He outlines two very crucial elements of ethical stories which enable them to be so educational in teaching us how to live a morally good life: the encouragement of challenging preconceived ethical norms and the universality of stories. Mitchel’s critical comparison shows us that no matter how ancient stories may be, they will always have relevance in the contemporary world.

The importance of self-discovery and individual progress in ethical stories

The second journey in which Gilgamesh partakes in is the more morally significant of the two. This journey begins with Enkidu’s tragic death, inspiring Gilgamesh in his failed search for immortality. Gregory presents us with a similar story in which fear of death is also overwhelmingly present[15].

He claims that King Lear’s “existential despair… hits us like a heart attack”[16], highlighting the way in which stories evoke passionate emotions towards ethical dilemmas. Perhaps the most frustrating part of the whole epic is Gilgamesh’s lost opportunity at gaining immortality when he loses the Gods’ plant.

As most heroic journeys (like Homer’s ‘The Odyssey’) are successful in their quests, what shocks us as modern readers is how Gilgamesh’s immense efforts to obtaining immortality prove to be a waste of valuable time in his finite life. This is especially emotional when Gilgamesh, “blinded by weeping”[17], admits defeat.

Through his failed journey, we come to understand the key moral message of the entire epic: the acceptance of mortality and the meaning of life. This is most evident when Gilgamesh returns to the city of Uruk empty handed and realises that his destiny was “not… everlasting life”[18] but to be a good ruler and assume his societal role as king.

Fasching praises this second journey as “the original model of ‘the quest’… to seek what is good not just for himself but for others”[19]. However, Fasching may be overexaggerating Gilgamesh’s supposed “selflessness”[20]. Gilgamesh seeks this quest due to his own fear of death and the misery caused by his loss of Enkidu, abandoning his citizens.

Therefore, whilst Fasching is correct in acknowledging Gilgamesh’s courage, he ignores Gilgamesh’s immense character development during the quests. Gilgamesh begins, like most humans, frightened of the possibility of non-existence. Only when he is forced to face his mortality does he realise what constitutes a moral life that is worth living.

This second moral journey Gilgamesh completes lacks the traditional struggle between good and evil and instead focuses on mortality and meaning. The epic cleverly presents us with the challenge of deciding what is most meaningful within our own lives.

Is it pointlessly defeating a monster for glory or coming at peace and understanding with one’s finite position within the cosmos of being? Gilgamesh answers this question for us when he returns changed after his final journey. Stories like Gilgamesh’s can “help shape [the] ethos”[21] of individuals when they partake in the character’s development as well as making their own critical decisions.

Indeed, it is never explicitly stated that Gilgamesh’ final quest is most significant. The poet simply assumes that readers will come to their own conclusions and choose the journey of ontology over a battle.

Perhaps this is what makes stories so detrimental for individuals as they grant autonomy and critical thinking, instead of making them moral robots who follow established systems of thought.

Hero vs heroine

Most ethical stories seem to follow a strict structural pattern. Campbell’s model of heroic journeys[22] serves as a template for “the psycho-spiritual development of… individual[s]”[23]. The journey begins with “a call to adventure as the hero passes unknown realms… and confronts adversaries.”[24] Gilgamesh’s journey conveniently aligns with this template, showing us that an ethical journey is required for a character to develop into a good moral individual. As we continue to read, we too go along this journey, progressing ourselves and learning from the story’s challenges.

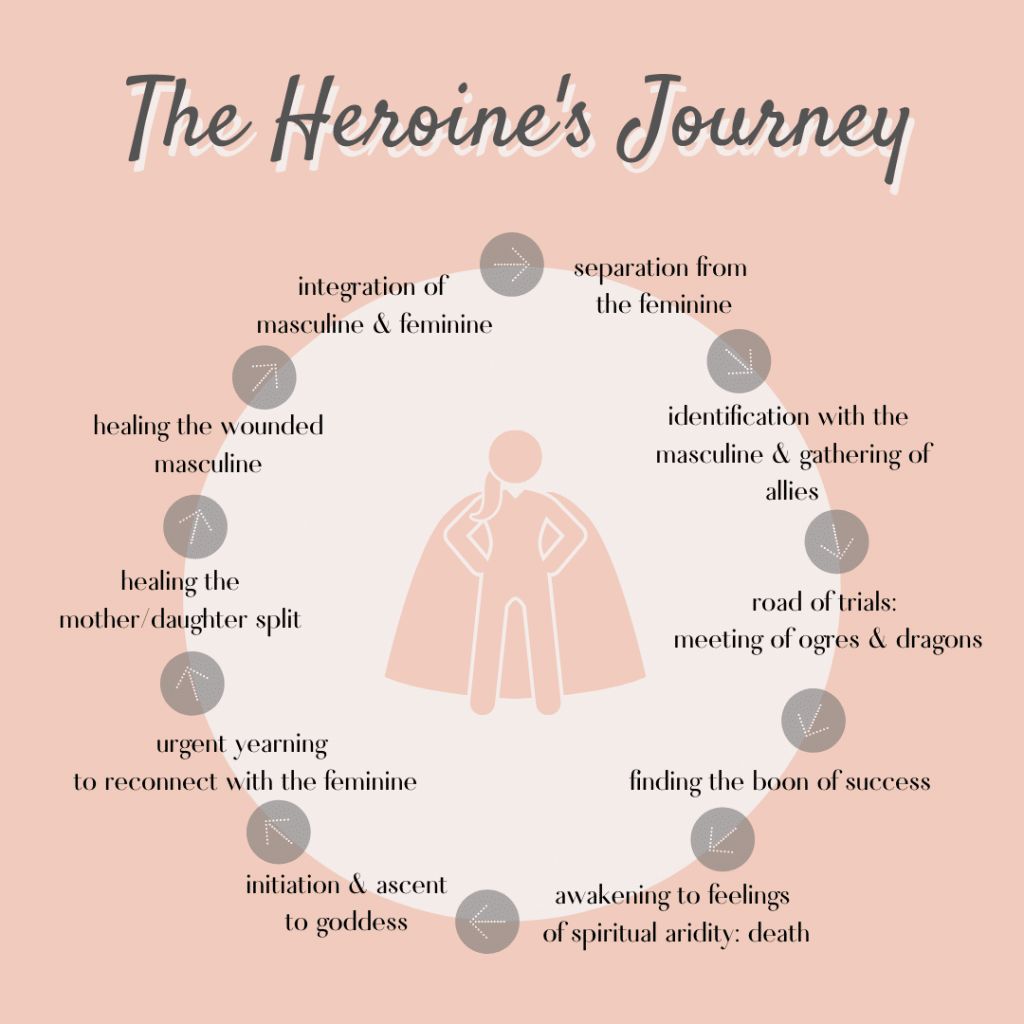

Although this journey seems to be universal for heroes, Murdock outlines its absence of heroines[25]. Unsatisfied with Campbell’s response to the absence of women in his model (“Women don’t need to make the journey… she’s the place”[26]), Murdock created ‘The Heroine’s Journey’[27].

The cyclical structure offers us with a fresh pair of lens on how women undergo transformation in stories, reflecting their struggles and adversaries[28]. The final and, arguably, most important stage is the “sacred marriage of the masculine and feminine”[29] in which the heroine assumes her identity, without denying any aspect of herself.

Indeed, Murdock criticises the way stories are so deeply imbedded in patriarchal societies, ignoring women’s journeys[30]. Perhaps with time, templates such as Murdock’s will allow narratives to become more inclusive and educate us equally on how to become better people. Therefore, we must accept that stories may lack representation, although there is a great capacity for improvement.

Ethical theories vs ethical stories

In order to show how significant ethical stories are in understanding how to live morally, they must be compared and contrasted with ethical theories. Although one may argue that theories hold superiority over stories due to their emphasis on rules and systemic approach, this is not entirely the case.

Perhaps the greatest reason for this is due to the creative and immersive ways stories approach moral dilemmas. Instead of being subject to following dogmatic theories blindly, stories encourage their readers to place themselves within unexpected situations and form their own unbiased opinions.

Arguably, stories may even become the antithesis of ethical systems and laws as story lines tend to directly challenge presupposed beliefs formed by such systems in the first place. Furthermore, theories tend to focus on imprinting rules on moral agents without any personal connection to them. Perhaps, this lack of awareness and understanding is the root cause of why people break the law as easily as they follow it.

Gregory highlights children’s moral education through stories as they constantly “absorb stories [from their] parents… fairy tales, and myths”[31], formulating a deeper understanding of morality. He also emphasises the impact of Biblical stories, stating that “thousands of hellfire sermons and hymns… demonstrat[e]… the power of vivid language”[32]. Therefore, in contrast to moral theories, the creative and immersive elements of stories show individuals what a moral action is instead of telling them.

The importance of ethical stories can be seen within modern fiction as well. Tahir Shah’s Arabian Nights [39] goes “in search of Morocco through its stories and storytellers” [40], highlighting the immortality of moral stories as they preserve sociological tradition. Stories are kneaded through time and space, moulding small details to apply to each cultural norm whilst preserving their key moral messages.

“The stories are like encyclopaedias store houses of wisdom of knowledges ready to be studied, to be appreciated and cherished. To him, stories represented much more than mere entertainment. He saw them as complex psychological documents, forming a body of knowledge that had been collected and refined since the dawn of humanity.” [41]

It is precisely the timelessness of Gilgamesh’s Epic that amazes most readers when they come across it. Problems of love, death and war are still as relevant as today as they were thousands of years ago.

Ethical stories may also be more convincing due to their relatability. Although Gilgamesh is “two-thirds divine”[33], Mitchell argues that he “considers himself fully human”[34]. He is still a finite being struggling with existential dread, a universal experience, and his raw emotional reaction to Enkidu’s death proves to be touching.

Gregory cleverly writes that “stories invite… responses of emotion, belief and judgement”[35]. As readers, we can relate to Gilgamesh’s struggles and connect with his quest in self-awareness[36].

Hence, we see that stories can connect to us deeper than theories ever can, as we form a personal connection to them. A person can have a favourite story, yet they usually don’t emotionally attach themselves to a moral theory; it is simply the one they choose to obediently follow.

Ethical stories as mediums for imagination and critical thinking

However, stories are not a perfect means of moral education. Ethical stories often grant too much autonomy to the individual and their application and understanding may be entirely wrong, naïve or simply not what the author intended.

Using Gilgamesh as an example, a reader may as well have deducted that Gilgamesh’s victory over Humbaba is greatly justified, while another reader may remain unsatisfied with the ending as Gilgamesh ridiculously loses the plant of immortality.

However, Gregory claims that a “story can only extend invitations, not coerce effects”[37] and individuals must accept accountability for their biased interpretations with stories, as they do with their own ethical choices.

He also points out that Plato and Locke believed that stories are “inadequate for individual morality or social justice”[38], perhaps because one may begin to neglect the world around them. Theories can be seen to encourage us to look externally, whereas stories absorb us in imagined and ancient realms.

Ultimately, we must understand the risks of stories when using them as a form of moral education, whilst acknowledging the overall positive impacts they have on relaying meaning to individuals. Gilgamesh’s multiple journeys serve as an example for the value of stories and are analogous to our own troubles, especially in our consumerist and digitally networked societies.

Stories as a form often support the idea that ethical dilemmas should be approached as puzzles to be solved rather than systemic errors in our societies. This is not to say that ethical theories aren’t necessary in aiding moral decision-making and maintaining social order.

The law will always hold us morally responsible, but perhaps the empathy that arises from stories will teach diverse audiences why we must be responsible.

Therefore, it would be foolish to claim that one can exist without the other as both aid each other – ethical systems clearly guide us, while stories hold individual value to our personal journeys through their fluidity and uniqueness.

Bibliography:

- Campbell, Joseph, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2004).

- Fasching, J. Darrel, Dell deChant, and David M. Lantigua, Comparative Religious Ethics: A Narrative Approach to Global Ethics, (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2001).

- Gregory, Marshall, Shaped by Stories: The Ethical Power of Narratives, (Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009).

- Leeming, David A., Encylopedia of Psychology and Religion, (Switzerland: Springer Cham, 2006).

- Mitchell, Stephen, Gilgamesh: a new English version, (London: Profile Books Limited; Profile Books, 2005).

- Sandars, N.K, The epic of Gilgamesh, http://www.aina.org/books/eog/eog.pdf [accessed 22 September 202

[1] Marshall Gregory, Shaped by Stories: The Ethical Power of Narratives, (Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009), p. 17.

[2] Darrel J. Fasching, Dell deChant, and David M. Lantigua, Comparative Religious Ethics: A Narrative Approach to Global Ethics, (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2001), p.85.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 93.

[5] Ibid., 86

[6] Mitchell, Gilgamesh, p. 10.

[7] Fasching, Comparative Religious Ethics, p. 86.

[8] Fasching, Comparative Religious Ethics, p. 93.

[9] N.K. Sandars, The epic of Gilgamesh, http://www.aina.org/books/eog/eog.pdf [accessed 22 September 2024], p.10.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Mitchell, Gilgamesh, p. 31.

[12] Ibid., p.30.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., p.26.

[15] Gregory, Shaped by Stories, p.12.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Sandars, Gilgamesh, p. 22.

[18] Sandars, Gilgamesh, p.10.

[19] Fasching, Comparative Religious Ethics, p.95.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Gregory, Shaped by Stories, p. xiv.

[22] Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2004).

[23] Maureen Murdock, ‘The Heroine’s Journey’ , in Encylopedia of Psychology and Religion, ed. by David A. Leeming (Switzerland: Springer Cham, 2006), pp. 1.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid., 2.

[29] Ibid., 4.

[30] Ibid. 2-5

[31] Gregory, Shaped by Stories, p. xiii

[32] Gregory, Shaped by Stories, p.9.

[33] Sandars, Gilgamesh, p. 3.

[34] Mitchell, Gilgamesh, p. 27.

[35] Gregory, Shaped by Stories, p. 1.

[36] Fasching, Comparative Religious Ethics, p. 93.

[37] Gregory, Shaped by Stories, p. 3.

[38] Ibid., p. 21.

[39] Tahir Shah, In Arabian nights, (Great Britain: Transworld Publishers, 2009)

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid. p., 15

Leave a comment