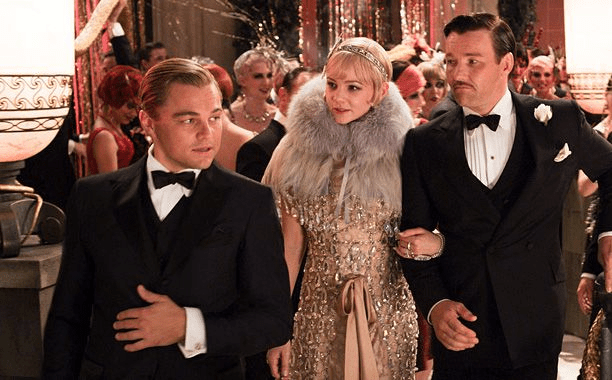

Published on April 10, 1925, The Great Gatsby turns 100 this year and its legacy as one of the greatest American classics remains untouched. In honour of this anniversary, I explore the presentation of morality across Fitzgerald’s most renowned texts, assessing the extent to which he aligns with Nietzsche’s moral philosophy.

Introduction

Nietzsche advocated a hybrid ethics of virtue geared towards higher men whilst condemning normative moral systems whereas Fitzgerald’s portrayal of a corrupted, hedonistic leisure class during America’s ‘Jazz Age’ could be read as reproachful of ensuing moral decay. However, Fitzgerald’s visions seem nihilistic in a chaotic world where the antagonists lack punishment and the protagonists often disintegrate despite any traditional virtues they possess.

If Fitzgerald practises authorial intrusion, the evidence suggests he has consciously integrated Nietzschean philosophy as he sought to abolish rigid moral norms reaffirmed by deep-rooted American tradition in a manner which can be traced to Nietzsche’s will to go ‘beyond good and evil’. It is society’s absorption with pleasure, disintegration and destruction which must be demolished whereas transgressing moral norms should be encouraged in the name of achievement and enterprise. I explore this Nietzschean reading through The Beautiful and Damned, The Great Gatsby and Tender is the Night.

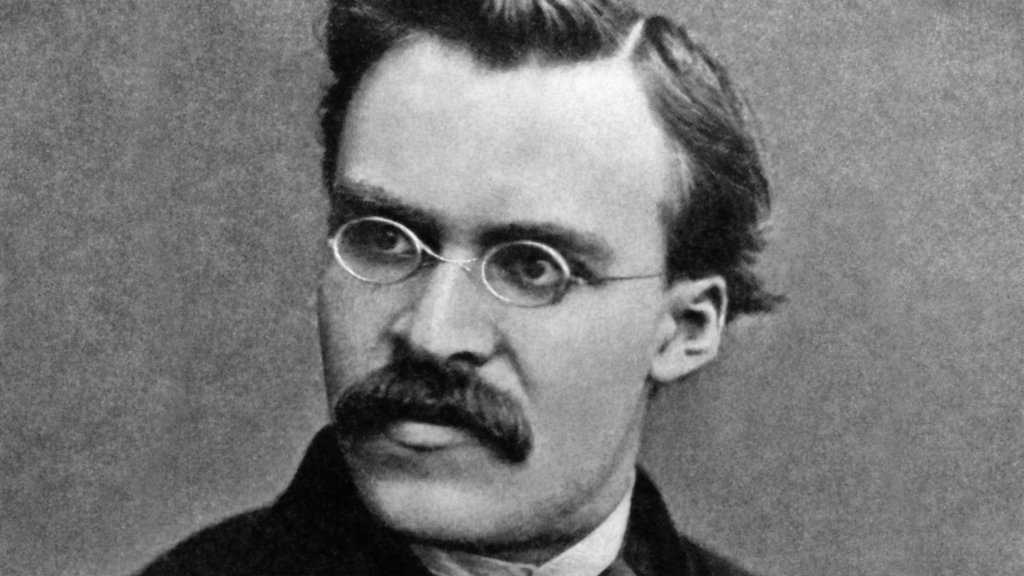

Nietzsche’s view on morality

Friedrich Nietzsche criticised normative moral systems on the grounds that we can never know another’s intentions, in terms of absolute deontological theories considering the nature of one’s actions, as well as through rejecting relative, teleological systems because determining an action’s consequence is impossible since the chain of causality is infinite.[1] Moreover, he took a fatalistic view, claiming that as we are not free moral agents we also have no moral responsibility. This idea perhaps aligns with many of the hedonistic, reckless protagonists in Fitzgerald’s texts who seemingly thrive in disastrous chain reactions of their own making when deviating from moral norms.

They possess vices and virtues from a normative viewpoint, whereas Nietzsche could condone this ‘good’ and ‘evil’ as necessary in the development of the personality since “between good and evil there is no difference in kind, but at times the most of one degree”,[2] which suggests that apparently good actions are sublimated evil ones whereas evil actions are brutalised good ones, an arguably prevalent idea embodied in the ‘New World’ non-fictional aristocrats who are characterised in ‘The Great Gatsby’, ‘The Beautiful and Damned’, ‘Tender is the Night’ and, to a lesser extent, ‘The Last Tycoon’.

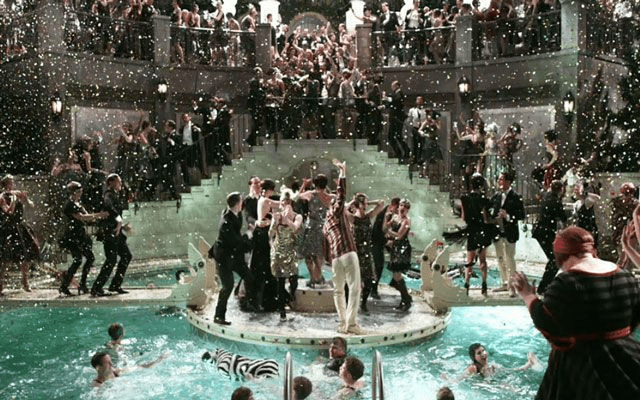

Although they possess some admirable qualities, sometimes in the form of courage or repentance, the emergence of frivolity from the equivalent of an upper class in the USA stemmed from their egotistical nature and an arrogant belief that their status as patricians from long-established families imbued in them the inherent right to disregard others merely to satisfy subjective desires, gallivanting their way through ‘The Jazz Age’. In retrospect of Nietzsche’s aforementioned words, their ‘moral’/’immoral’ qualities seemingly allow for behavioural complexities that complement the chaotic plots. Inadvertently, the protagonists’ thinking may be ethically teleological (consequential) in action scenes, however this is translated on a wholly subconscious level so that Fitzgerald practically presents them as anti-realist about morality in the way that Nietzsche asserted there is a lack of objective moral truths.[3]

Traditional Christian morality could potentially use ‘The Great Gatsby’ to warn what transpires when the upper class and criminals form a social order of dilettantism by cultivating pretentions of superiority while the progression of events leads to a fatal tragedy including murder, manslaughter and suicide (all ‘sinful’) which become increasingly dreadful because of the ‘immoral’ excuses leading up to the deeds.[4]

However, whilst Nietzsche doesn’t want to transform the whole of society, his esoteric morality contrastingly aims at freeing higher beings from their false moral consciousness (belief that morality is good for them). He writes in his preface to ‘Daybreak’ that “In this book, faith in morality is withdrawn-but why? Out of morality!” The herd restricts the superior, independent human spirits from whom he thinks greatness can arise4; perhaps, Anthony and Gloria’s attainment of their fortune (‘The Beautiful and Damned’) comes forth because of their ignorance of the ‘herd’s’ restrictions, rather than despite it. Their selfish drive is meritorious irrespective of the emotional bankruptcy and mental/physical corruption accompanying their prosperity.

Likewise, Richard’s life deteriorates not because of his moralities, but perhaps due to his failure to live up to their restraining standards. Leiter claims that Nietzsche doesn’t attack any specific normative system such as Christianity or Utilitarianism, but sometimes all of them. He doesn’t confine his criticisms to one religious, philosophically or historically circumscribed example as all normative systems embrace norms that harm the ‘highest’ men in benefit of the lowest. 5 I will be examining to what extent a Nietzschean perspective of Fitzgerald’s texts would approve the ‘moralities’ of the characters presented and whether they conform to a ‘lower’ or ‘higher’ morality, as well as how this differs from a normative reading.

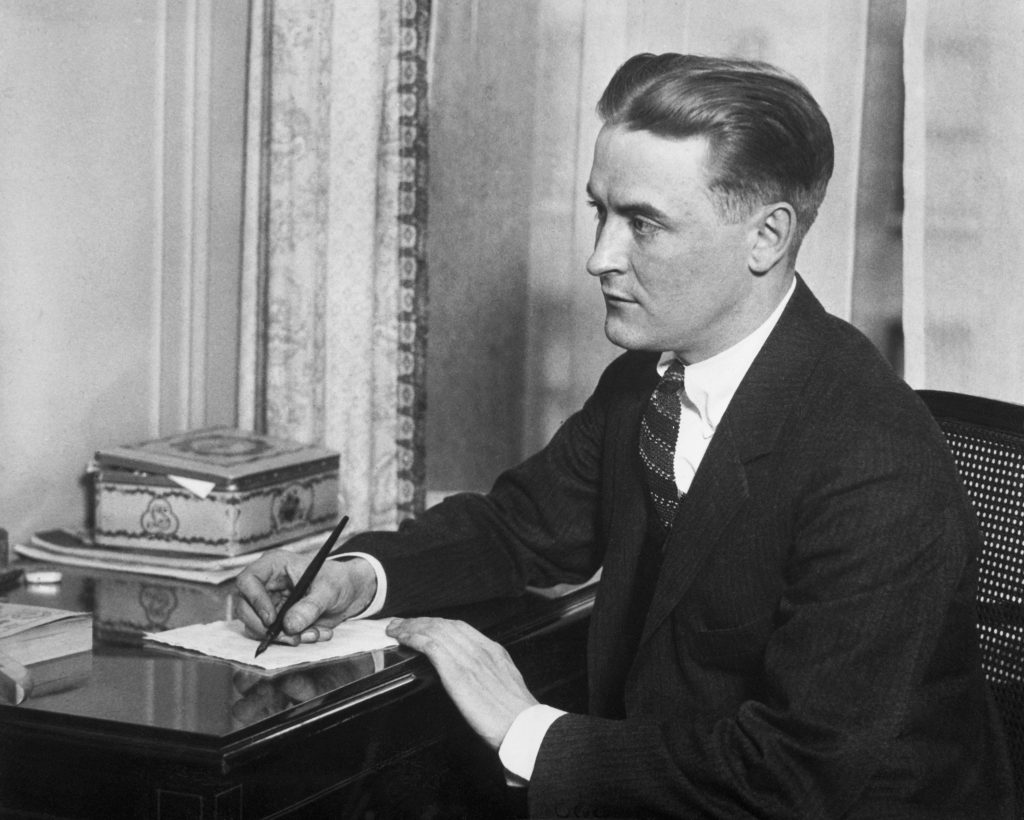

Was Fitzgerald a Nietzschean?

Fitzgerald’s intentions towards how the reader should respond to the character’s depravities are open to interpretation. Cheshire alternatively argues that Fitzgerald’s novels provide windows where elements of past American society had drowned themselves in an ethical slump.[5] In light of this view, the appeal to the reader derives from the luxury to live vicariously through the decadent and dishonourable whilst simultaneously finding relief in ridiculing those deemed irrational and beguiled. Through partaking in moral judgement, the readers themselves adhere to the unquestioned moral views discarded by Nietzsche, ironically falling into the category of the ‘lower’ herd who restricts the character’s ethics. However, the conclusion that Fitzgerald holds contempt towards those he writes about is far too simplistic.

The ‘Beautiful and Damned’ could be seen as a ‘self-morality play’ because the sub-society described is self-contained and destined to destroy itself 7 through the depiction of New York’s Café Society as shallow, excessive and flawed. While Fitzgerald’s view is unsympathetic, he isn’t necessarily condemning the characters’ immorality, partly because ‘Tender is the Night’ and ‘The Beautiful and Damned’ are essentially autobiographical. Whilst all the novels share an element of ensuing moral decay, the characters’ personal disaster arises from their lack of objectivity in life, failing to extract themselves from external and internal indulgences. As an amateur psychoanalyst himself, Fitzgerald’s novels could also be read as a dissection of human nature masking anxieties, needs, neuroses, failures and, of course, ‘immoralities’.

Much like Nietzsche’s philosophies, his novels could be likened to confessionals as he lays down his human flaws and reflects his own weaknesses; Fitzgerald was known to have financial problems arising from frivolities and turned to other women to satisfy his carnal desires.[6] Whilst a Nietzschean perspective would discredit an idea that his life was usurped by a lack of ‘morality’ he certainly struggled to be the ‘higher’ man who was solely work-orientated. This context suggests the texts are not merely moral fables and some of Nietzsche’s philosophies are likely to be integrated into his own work.

The degree to which Fitzgerald was actively influenced by Nietzsche in his presentation of morally anomalous characterisation is not empirically documented. However Bruccoli’s ‘Conversations’ claim that “F. Scott Fitzgerald is a Nietzschean… in a state of cosmic despair” and had been “a hot Nietzschean ever since he read ‘Thus Spake Zarathustra”[7] ,the format of contemporary interviews adding to the reliability of this claim as it depicts direct quotations by Fitzgerald. This is supported by accompanying scholarly views including Ollson’s belief that Nietzsche’s influence of Fitzgerald’s ‘complex philosophy of culture’ was even present in his early short stories [8]along with the idea that this infusion of Nietzscheanism was conscious; he was not an “innocent to philosophy’ as some may believe (Fosher, 22)10.

Significantly, in a 1923 interview, two years after ‘The Great Gatsby’ was written’, he listed Mencken’s ‘The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche’ as his second favourite book, revealing that Nietzsche was “one of the intellectual influences which moulded Fitzgerald’s mind” (Bruccoli, Conversations 44)9 which further demonstrates this conscious integration of Nietzsche’s attitude into his later novels. In fact, his appraisal of 20th century American culture is almost ironically similar to Nietzsche’s disapproval of the ‘herd’: “But taken collectively, he (the American) is a mass product without common sense or guts or dignity” connotes a criticism of the proclaimed ‘lower man’ who fears using his ‘guts’ (courage) to violate moral values for his own ‘dignity’.

His urge for the ‘mindless race’ to surrender by “going into a period of universal hibernation and begin all over again” parallels Nietzsche’s belief that the herd’s lower nature, weakened by morality, degrades all of mankind who inevitably act like the ‘sheep’ Fitzgerald speaks about. Furthermore, the two ‘higher men’ Nietzsche praised (Goethe and Beethoven)[9] are Fitzgerald’s exact examples given in his claim that “we threw up our fine types in the 18th century, when we had Beethoven and Goethe”9.

This emphasises his own likely aspiration to become that which Nietzsche praised perhaps because Nietzsche’s moral system of relativism was gradually taking prevalence in the period of Fitzgerald’s writing. He was a vociferous social critic of 20th century USA, when Victorian moral values were being re-evaluated[10] and change was also a primary concern for American people. Even at age 20, Fitzgerald seemed an advocate of this higher morality, wanting to be “King of the World, a sort of combined …Abraham Lincoln and Nietzsche”.[11] Therefore, the elements of moral controversy within the texts may well be a product of direct Nietzschean influence.

Conversely, Nietzsche’s introduction to the US scene was marred by early misconceptions of his works through distorted translations and the fact that the first of his books received by the public were some of his last, such as ‘Thus Spake Zarathustra’, a likely influence of morphine or the product of a madman according to some readers. Likewise, his 1888 books are ‘imbued with such inflated conceit that it cannot be decided for sure whether the author had been under the influence of a more potent strain of narcotics, or whether his mental state was rapidly eroding, or whether both of these factors existed side-by-side’[12]. Therefore, according to Putz, the understanding of his philosophy could have initially veered on negative and been interpreted, even by Fitzgerald, as an exhibition of his ‘degeneracy’12.

Irrespective of Fitzgerald’s personal philosophical attitude, the singular direct reference to Nietzsche in his fiction lies in ‘The Beautiful and Damned’, where “Gloria had developed into a consistent, practising Nietzschean” “because she was brave, because she was spoiled, because of her outrageous and commendable dependence of judgement, and finally because of her arrogant consciousness that she had never seen a girl as beautiful as herself”.

This repeated listing of cynical qualities is drawn from the fact that she complains about cafés and refuses to contribute to housework, instead inflicting all duties upon her husband. In this respect she from the stereotypical female of 20th century patriarchal culture where gender roles were doubtlessly established. Yet, because of her strength (‘arrogant consciousness’), ‘bravery’ and relentless use of her advantageous beauty, she is exempt from laborious, ‘lower’ occupation. From the audience’s viewpoint, Fitzgerald seemingly attributes undesirable character traits such as ‘spoiled’ to Nietzschean philosophy as he was possibly a victim of disfigured interpretation on behalf of translators.

Yet, Gloria’s ability to transcend sexist thinking for the sake of self-interest is ‘commendable’ along with the ‘Nietzschean Incident’ in which her ‘sincere and profound independence’ is astutely exhibited by the tremendous amount of “energy and vitality (which) went into a violent affirmation of the negative principle ‘Never give a damn. Not for anything or anybody except myself’. As the novel’s victor, Fitzgerald applauds Gloria’s Nietzschean practise, reiterating her principle recurrently: in Maury’s monologue the ‘wise and lovely Gloria’ is applauded for being born knowing the significant philosophy of ‘the tremendous importance of myself to me, and the necessary one acknowledging that importance to myself’.

She later acts as an intelligent, ‘immoral schoolmistress’ in persuading Anthony to partake in nihilistic thought since “on gray mornings… they could…smile at each other and repeat, by way of clinching the matter, the terse yet sincere Nietzscheanism of Gloria’s defiant ‘I don’t care!’” Both her existentialism and egotism, while perhaps resented by some readers, reaffirm Fitzgerald’s positive appraisal of Nietzsche’s moral vision. Therefore, Putz’s summary of Fitzgerald as an ‘aspiring Nietzschean’[13] arguably holds prevalence.

Higher morality & higher men vs traditional ethics

Notably, Nietzsche was not a critic of all ethics, explicitly embracing the idea of a ‘higher morality’ which could inform the lives of ‘higher men’ (Schacht 1983, 406-409)[14]. He aimed to offer a revaluation of existing values in a manner that appears to involve appeal to broadly ‘moral’ standards of some sort.[15] Nietzsche’s positive ethical vision offers no systematic guidance on how we ought to live but focuses on developing genuine virtues specific to individuals so that one’s own morality is created using laws of science and ideas of determinism in order to become a creative higher man.

Conventional morality is not a plausible set of criteria for all to follow considering the existence of natural ‘type facts’ (the fixed psycho physical constitution which defies one’s personality) determining the particular conditions under which different agents flourish.16 ‘Higher men’, which contrast from the masses, require a moral diet not detrimental to their excellence, unlike normative ethics which propel anti-nature principles and teach men to “despise the very first instincts of life” by incriminating self-love and conditioning men “to experience the presupposition of life, sexuality as something unclean”.[16]

Sex & Hedonism in Fitzgerald & Nietzsche

Certainly, an aspect of the pervading ‘moral’ corruption inhibiting most of Fitzgerald’s characters is their whole-hearted acceptance of their ‘natural’ and ‘sexual’ instincts through their embrace of infidelity. Those who maintain faithfulness lack reward therefore often succumb to some other transgression of Christian values and also avoid the ‘deadly war’ waged by morality to higher beings.[17] In terms of sexual liberty, the whole ‘world[18] and its mistress returned to Gatsby’s house…while church bells rang’; the juxtaposition symbolises a collective disregard for morality which determines “sexuality as something unclean”. The accepted morality’s prohibitions are of no concern to Nietzsche whereas the implied instances of sexual behaviour would have been repugnant to some contemporary readers.

Moreover, what does contain intrinsic value for Nietzsche is human excellence, placing value on the flourishing of higher men rather than the happiness, altruism, equality, pity/compassion 16(which many of the characters indisputably lack) glorified by most moral systems. In actuality, these qualities are extrinsically valuable for the cultivation of human excellence and a culture in which such norms prevail will be one eliminating the conditions for the realisation of supremacy.

Nietzsche explicitly opposes hedonism and utilitarianism[19] because happiness is “a state that soon makes man ridiculous and contemptible”[20], perhaps rendering the avarice displayed by New York’s leisure class as proof of hedonism’s ‘despicable’ consequence, especially in ‘The Beautiful and Damned’ and ‘The Great Gatsby’ where ‘comfort and happiness’ are only limited and finite prospects (in the sole pursuit of immediate superficial gratification on behalf of the majority, people are left only with misery).

Nietzsche allows that he himself and the ‘free spirits’ will be ‘cheerful’ but if happiness is what one aims for, they are not to be deemed worthy of admiration because “the discipline of suffering, of great suffering has created all enhancements of man so far’. Pain is a prerequisite for profound achievement and therefore for the cultivation of human excellence; he generalised from his own experience of physical suffering which coincided with his greatest productivity.

Nietzsche opposed morality’s power to dominate the nature of a culture with potential for great achievement, compelling individuals to avoid suffering as they have internalised the norm that happiness is the ultimate goal which encourages people to waste energy pursuing pleasure.[21] In this respect, the majority of characters are exempt from the status of ‘higher men’ particularly in utilisation of alcohol as a catalyst for oblivion and exaltation, one of Fitzgerald’s own self-confessed pitfalls.

In ‘The Beautiful and Damned’, while Richard Caramel reprimands Anthony for being a pessimist and paradoxically holding the view that “happiness is the only thing worthwhile in life”, Anthony ironically craves a drink because “his pleasure in the conversation had begun to wane”, multitudinously avoiding any chance for uncomfortable intellectual enlightenment simply for momentary physical gratification. Fitzgerald criticises this debauchery, the alcohol leading to Anthony’s demise as he mentally and physically deteriorates to the requirement of a physician and a wheelchair (simultaneously losing health, another aspect of the ‘higher man’). His final thoughts consist of “the hardships, the insufferable tribulations, he had gone through… He had been exposed to ruthless misery.”

Who are Fitzgerald’s ‘higher men’?

This is a practically tragicomic notion to the reader who is aware of the absurdity of Anthony’s incongruous appeal to possessing some sort of ‘higher’ dignity through his false affirmation of successfully enduring ‘ruthless misery’. He becomes a pathetic parody of what he initially aspired to be in avoidance of social norms. Similarly, the protagonist in ‘Tender is the Night’ attempts to avoid (work-related/domestic) problems in his pursuit of the alluring Rosemary and incessantly abuses ‘liquor’, which he is chastised for by a recovering patient’s father.

However, his stronger will and work-ethic allows him to be a ‘higher man’ than Anthony as well as many of the other sybaritic characters dispersed throughout the texts because “dismissing a tendency to justify himself, he sat down at his desk and wrote out, like a prescription, a regime that would cut his liquor in half”. He reasons that “doctors, chauffeurs and Protestant clergymen could never smell of liquor” rather than basing his decision on some external perspective or morality. Richard’s responsibility is demonstrated as he doesn’t cling to excuses surrounding his emotional suffering which promoted his addiction, ‘blam(ing) himself only for the indiscretion”.

Despite his initial weakness, Richard behaves in a correlative way to Nietzsche by self-monitoring his intake rather than yielding to blind pleasure; Nietzsche himself only drank water (and milk on special occasions) and he labelled alcohol and Christianity as the “two great narcotics in European civilization” (coinciding with the European setting of ‘Tender is the Night’); both numbed pain and reassured people that their lives were fine, sapping them of the will to achieve and excel by giving them transient feelings of satisfaction rather than the means to improve.[22]

Anthony fails to meet the ‘higher man’ criteria but, despite divulging in lower pleasures, he seems to condemn the ‘lower moral classes… who are pictured in the comics as ‘the Consumer’ or ‘the Public’”, because of their ‘herd’ mentality and meaningless hunt for lower pleasures. Perhaps, Fitzgerald’s authorial intrusion comes across also in ‘The GreatGatsby’ where Nick judges the excessive materialism-Fitzgerald doesn’t criticise society’s defiance of New Testament’s teaching which asserts humble modesty, but rather the ‘lower’ human’s downfall due to New York’s growing hedonism which is often represented by abundant wealth.

Myrtle exploits Tom’s desire to gain money and material goods, Gatsby is partially infatuated with Daisy’s ‘voice full of money’ and Daisy is seduced by Gatsby’s display of wealth (expensive shirts). In their craving for artificial happiness, they may challenge morality but not in an attempt to become ‘higher’ people, only in a pleasure-seeking (not even utilitarian) format, which is apparently unacceptable to both Nietzsche and Fitzgerald.

Additionally, the higher man is solitary and deals with others instrumentally because he is consumed by his work/responsibilities. “A great man is incommunicable… he finds it tasteless to be familiar” and lacks the ‘good-naturedness’ so often celebrated in popular culture. [23]Undeniably, the characters depicted often treat each other as a means to an end in their relationships, transactions and general demeanour.

Yet, despite violating the so-called intrinsic value of individuals at times, they are sociable and dangerously dependant on others as Anthony, Richard, Nick and Gatsby (the heroes of their novels) are lonely. Richard (‘Tender is the Night’) eventually resides in solitude, separated from his family, as it is concluded that “in any case he is certainly in some section of the country, in one town or another” whereas he begins by “caring only about people”. Similarly, Anthony (‘The Beautiful and Damned’) “had lately learned to avoid loneliness” by routinely hurrying to “one of his clubs to find one” person. His weakness is repeated throughout as he later again “found in himself a growing horror and loneliness” even “in preference din(ing) often with men he detested” out of fear of eating, living and thriving alone. As the plot progresses, his need for human contact only increases; he “no longer craved the warmth and security of Maury’s company” which would, at least from a Nietzschean perspective, allow for intellectual debate.

Instead, he is entirely reliant on his romantic interest, allowing Gloria to “pull an omnipotent controlling thread upon him”, relinquishing his own responsibilities despite his helpless realisation that “already she had tainted too many of his ways”. Gatsby himself catastrophically succumbs to the same woman twice in full knowledge “that when he kissed this girl… his mind would never romp again like the mind of God”. He recognises that a lack of solitude would lead to less power, significant as he is depicted with God-like qualities before his usurpation by Daisy. He gains Nick’s admiration by exerting the influence of his smile which “was one of those smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it” that “seemed to face the whole eternal world”, the heavenly imagery suggesting an aura of immortality that leads to the contrasting mortality made apparent in his death; he was only a higher man in solitude. Likewise, Nick “felt a haunting loneliness” in himself and other ‘Wall-Streeters’ who hoped to escape ‘solitary dinners’ and the immensely ‘poignant moments’ of life caused by solitude. This feeling is perhaps the root of his socialisation with the acquaintances whose ruin he observes.

Ultimately, Anthony disintegrates into a completely pathetic figure due to the fact that “He could say ‘No!’ neither to man nor woman”. He virtually scrapes the bottom of what befits the lower man. Yet, while Anthony’s individual impulses are uncontrollable, Fitzgerald’s own philosophy is integrated into ‘The Beautiful and Damned’ [24] as the third person omniscient perspective mocks “a land where… rulers have minds like little children … where ugly women control strong men”. This interruption of the plot reaffirms to the reader that Anthony exemplifies the latter; he is a lower man the author disapproves of along with the country’s docile leaders.

Furthermore, the higher man practices solitude as a requirement for undertaking some unifying project, a burden which Stahr in ‘The Last Tycoon’ pursues to the impairment of his health as, despite present illness, he “apparently derived some rare almost physical pleasure from working light-headed with weariness”. This draws parallels to the keen psychologist in ‘Tender is The Night’ who “always had a big stack of papers on his desk” after discarding any semblance of a social life. Their dedication is in stark contrast to the idle men of ‘The Beautiful and Damned’ who wryly consider ‘writing’ and ‘science’ yet instead prefer to ‘sleep’ because “there’s nothing worth doing”.

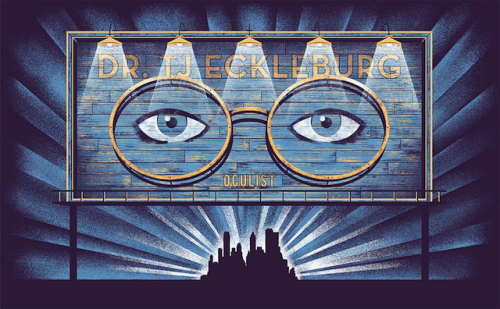

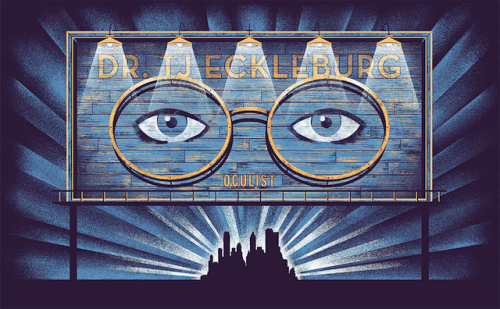

Even Richard, the amateur writer, abandons his dream, in favour of a ‘hot bath’. The irony lies in the pathetically climatic resolution found in Anthony’s exclamation that “It was a hard fight, but I didn’t give in” by submitting to ‘mediocrity’ (also known as ‘work’). His dignity is a product of delusion since he rejects the herd morality yet proves a lower man himself. Similarly, Wilson (‘The Great Gatsby’) represents the blind masses; he is blind to Myrtle’s affair and the characters’ true identities, an idea reinforced in his invocation of God as a symbol of moral authority by associating Dr. Eckleburg’s image with omnipotence and therefore accepting ‘without question the dictate of some supreme sage” (Mencken). [25] He is morally blind and spiritually ‘sick’.

However, while the men contain an array of higher/lower merits, Gatsby best exemplifies a master, rather than slave, morality in utilising qualities like courage, strong-will and self-worth which lead to an abundance of power. He creates an individual ethical sense through his misinterpreted status of honest wealth and obtaining any desire, honouring ‘the powerful man in himself’, whereas the ‘slave’ values humility and sympathy which transforms into resentment over time.[26]He is an isolated (even in death) and morally ambiguous figure who at times looks like “he killed a man” and is just as much an adulterer as Tom while also contributing to the moral chaos of society by ruthlessly exploiting the law which forces Nick to face aspects of his own ethical nature.

Yet, through the medium of Nick’s oscillating responses to him, the reader sympathises with Gatsby’s role of victim which emphasises the incorporation of both strength and weakness. Nick’s role is arguably that of observer and judge because he is smug, at times, about his own ethical identity. He seemingly adopts an attitude of tolerance which implies detachment and disengagement from the plight of other people’s lives. The meaning conveyed by Fitzgerald could be that ethical principles, or at least a brake on one’s desires, are essential if one is to avoid inhabiting a world of different chaos where the ego prevails and where people like Tom and Daisy “smash things up and creatures”.

In retreating home to the Midwest as a region in which old traditions and values have always seemed to offer security in the past, he withdraws from the city which has challenged his sense of identity by its vying off of all moral constraints. Yet, he is compelled, even at the cost of his own moral integrity, to play a role in the confused situation of despair, betrayal and death due to his emotional commitment to Gatsby.

Alternatively, Nick can be read as an aspiring Nietzschean, since he reproved Wilson’s and the masses’ blind morality, as he opens the novel “inclined to reserve all judgements”. Instead, he searches for truth such as in his scepticism towards the herd’s speculations about Gatsby. This independence is supported by his proclamation that “I am one of the few honest people I have ever known”. He opposes mass morality’s ability to colour one’s perception of the truth. Rather than imposing moral judgements, Nick concedes that Tom’s actions were “entirely justified from his own perspective.” He concurrently holds an “unaffected scorn” for the majority of men, his elitist view aligning with Nietzsche’s criticism of the ‘labouring class’ and the ‘legal aristocracy’.[27]

The men may often discard a broader morality; Anthony is a primary example, criticising the acceptance of Christian ethics because we shouldn’t “cease to be impulsive, convincible men interested in what is ethically true by fine margins” and “substitute rules of conduct for integrity”. In light of this, he later aims to “assert himself as her (Gloria’s) master” by means of “sustaining his will with violence”. However, he doesn’t seek to ‘dominate’ for excellence, achievement or self-reverence but simply because her petulance had deprived him of a purposeless ‘pleasure’. The characters’ actions lack justification throughout and the accompanying aspects of the higher man are absent. Therefore, they would consequentially be criticised both in light of normative morality and Nietzsche’s moral perception, as presumably intended by Fitzgerald himself.

Toxic masculinity & sexism

Specifically, Nietzsche’s reproach focuses on the fact that our social concepts of good and evil are ‘weak and unmanly… weakening all our bodies and souls’[28], therefore his philosophy emphasises male excellence and power; the concept of ‘Übermensch’ only dubiously encompasses the idea of higher humans consisting of both genders as it focuses primarily on the super man. Moreover, “there is no wrong in unequal rights”, this being the natural state of modern civilisation. What is wrong lies rather in “the vain pretention to equal rights”. 24 This idea potentially attacks 20th century American ideals of freedom, equal opportunity and social/economic mobility which excluded marginalised minorities, including women, whom Fitzgerald often also disregards. Both Nietzsche and Fitzgerald arguably accept blatant sexism rather than viewing it as immoral or ‘wrong’.

Fitzgerald once defined ‘The Great Gatsby’ as ‘a man’s book, of purely masculine interest’[29] and perhaps was expressing a limited appreciation of female interests. Nevertheless, the ethical problems confronted are those only available to men in an affluent world.[30] He acknowledged that female characters are subordinate and unpopular with women who dislike being ‘emotionally passive’, aligning with Nietzsche’s rather chauvinistic claim that “one half of mankind is weak… ally-sick” and requires “a religion of the weak which glorifies weakness, love and modesty” in a manner which ‘makes the strong (men) weak’[31]; Gloria, Daisy and Nicole are technically the survivors at the price of the males despite seeming to be decorate figures of apparently fragile body.

Certainly, 1970s feminists depicted Nietzsche’s reputation for epitomising misogyny in his philosophy as utterly unacceptable. He was publicly accused of being a ‘hater’, ‘despiser’ and an anti-feminist ‘enemy’ of women especially since, with the emergence of World War Two, his philosophy was increasingly employed to ‘serve the Fatherland’ in encouragement of the fascist ideology of ‘motherhood’. [32]Similarly, a recent feminist critic charged ‘The Great Gatsby’ with exhibiting hostility towards women, a serious charge, in her proclamation that it is “not dead Gatsby but surviving Daisy (who) is the object of the novel’s hostility and its scapegoat”. [33]

Throughout the text, there isn’t a single female character who exhibits anything but a desire for pleasure and material possessions, neither comprehending Nick’s moral pre-occupations or his desire to understand Gatsby’s intense devotion to a dream which transcends his circumscribed self.[34] Fitzgerald often portrays the female as vain, egotistical and destructive. They are never capable of idealism or intellectual interest nor do they experience pain. Nietzsche also trivialises/sexualises any relationship a woman might have with a man: to maintain a friendship with a man ‘a little physical empathy is required’.28

This objectification translates to the sexual allure of women as a major feature of the novel, robbing women of personal interests. Daisy infamously deduces that “the best thing a girl can be in this world (is) a beautiful little fool”, suggesting that her daughter’s male-serving purpose is pre-determined before she hits puberty. Furthermore, Gloria in ‘The Beautiful and Damned’ “values” her body solely because Anthony thinks it’s ‘beautiful’, fearing that age or pregnancy will deter her from being socially desirable as her husband’s “baby” and ‘dangerous plaything’ (according to Nietzsche[35]).

And while Fitzgerald’s last novel, ‘The Last Tycoon’, shows some development through his first female narrator’s intent on navigating the political activities of Hollywood, even Cecelia’s “little sport of intellectual interest’ served to transform her merely into a ‘brilliant ornament’ as she literally objectifies herself because of her gender. She soon clarifies the minimal difference between actual women and actresses whose roles are dependent on men for pleasure, survival and life since the director stresses that “at all times, at all moments when she is on the screen, in our sight, she wants to sleep with Ken Willard” yet must give no impression of this intention unless they are “property sanctified”. The female, real and surreal, is required to obey ‘moral’ norms yet paradoxically also satisfy the male ego through appearance and intention. Women characters are marginalised into the purely personal areas of experience with no pretence of the currently accepted modern equality, which Nietzsche himself does not necessarily condone.

However, Fitzgerald’s claim that ‘the book contains no important women characters’31 is disputable as his fiction is clustered with emancipated women enjoying the new social/sexual freedom of the twenties. Tom Buchanan on the one hand advocates the old paternalism which subordinates women to the status of decorate objects of male desire yet Nick, as narrator, requires us to condemn his double standards existing in the form of his sexual affair with Myrtle Wilson.

Even his stereotypically sensual mistress lacks weakness in this context, disobeying imposed Christian glorification of chastity in order to dominate her husband who is “his wife’s man” rather than his own. Significantly, not all of the female protagonists possess passivity through their transgression from a feminine perspective on life to almost being characterised as ‘higher women’. Jordan Baker incorporates the traits of the higher man in ruling her life by independence, detachment and determination to triumph. There is the implication that she is androgynous, losing her femininity, and is morally suspect and “incurably dishonest” because “she wasn’t able to endure being at a disadvantage”.

She began ‘dealing in subterfuges’ and this ability to deceive in hopes of attaining a prospective goal places her in the category of a ‘master’ morality, positioned higher than Nick due to his ethical concerns. Equally, Nicole in ‘Tender is the Night’ thinks self-sufficiently through her conditioned belief that “either you think-or else others have to think for you and take power from you, pervert and discipline your natural tastes, civilise and sterilise you.” Not only does the direct theory of acquiring ‘power’ directly correlate to Nietzsche’s very definition of ‘master morality’ but her opposition to ‘civilisation’ is similar to Nietzsche’s belief that morality restricts our ‘natural instincts’.[36]

She further pits her “unscrupulousness against his (her husband’s) moralities”, finding his weakness abhorrent. Likewise, Gloria (the only character directly compared to Nietzsche) finds absolute morality intolerable as “I detest reformers, especially when they try to reform me”, which is perhaps why Anthony sees them both “equals” in matrimony. Her very aesthetic is reminiscent of the bourgeois women who bobbed their hair and held allegedly ‘nihilistic views’ after discovering the revelation of Nietzsche’s philosophy. This is also present in Gloria’s rejection of purity, motherhood and conventional wifedom which Nietzsche surprisingly dismisses because “women easily experience their husbands as a question mark concerning their honour, and their children as an apology or atonement”.[37] Therefore, despite feminist criticism, Nietzsche had become so popular among contemporary women that he was regarded as a ‘philosopher of women’. [38] While both Fitzgerald and Nietzsche see nothing immoral in slating feminine virtues, the women who “overhear a man’s world” and decide to interact in a ‘masculine’ pattern, “not strongly gendered either way”, are praiseworthy in their transgression of 20th century moral boundaries from a Nietzschean perception. Fitzgerald’s texts are primarily satirical with no pretentions of a male inner life either and many of the strongly misogynistic characters are antagonists. Therefore, the women presented are not wrongly unethical although their treatment might be considered slightly wrong, if not immoral, by both the author and philosopher.

The ‘death of God’, religion & existentialism in the Jazz Age

In Nietzsche’s ‘Parable of the Madman’, [39]he coins the sociological movement of marginalising the no longer relevant ‘God’ as ‘the death of God’- no one berates the madman for blasphemy or helps him find God. McGrath illustrates Nietzsche’s view that the former importance ‘God’ had in structuring our lives has ended: “God has ceased to be a presence in Western culture. He has been eliminated; squeezed out”[40]. Therefore, while Anthony (‘The Beautiful and Damned’) is rightfully nihilistic in his belief of “a meaningless world”, his negative nihilistic belief that to give life “purposefulness is purposeless” is opposed in its presentation by Fitzgerald and would theoretically be opposed by Nietzsche, who veered towards positive nihilism.

In his rejection of theism and the certainty and meaning it gave us, he states that the Christian God is no longer a credible source of morality, especially because He is the clearest symptom and cause of objectivist thought which undermines the meaning of our world for the sake of a fictitious reality (religion). However, this anti-realist, existentialist/nihilistic thought is a moment of celebration because we can now create subjective meaning in our lives deriving from our contextual involvement in the world rather than a projected, universal standard of meaning that stems from a belief in God and restricts our personal involvement in the world by enforcing slave morality on the individual.

Arguably, Fitzgerald’s characters seem to project a certain aspect of nihilism in their carelessness along with their attempt to create distinct existential ‘meaning’ surrounding a rejection of Christian teachings of poverty, modesty and sacrifice. Despite Fitzgerald’s Roman Catholic background, his presentation of theism in the texts correlates to Nietzsche’s own admonishment. The image of Dr. Eckleburg, whose eyes Wilson conflates with God, suggests that religious tradition instils a dangerous fear in the ‘slave’ who later irrationally rebels; Wilson reminds Myrtle that “God knows what you’ve been doing. You may fool me but you can’t fool God” whilst pointing to the billboard.

Yet, he later ‘sins’ through homicide and suicide, violating his earlier submissiveness and faux ideas of morality that are made even more absurd in his admission to Michaelis that he doesn’t attend a church or follow a specific denomination of Christianity. His ‘belief’ is a cultural, rather than personal choice and he succumbs to mass ideologies. Furthermore, Eckleburg was a later addition to the novel and likely correlated with the Nietzschean thought supplied to Nick and the other characters. Therefore, the symbol is contains a double meaning which signifies a misinterpretation of religious significance and an emphasis on the need to clearly interpret the world in order to promote the progress which Fitzgerald also feared was at stake with the death of ‘individualism and the vitality of the creative spirt’.[41]

The repetition of this motif displayed in Eckleburg’s ‘dimmed’ and ‘brooding eyes’ in the events leading up to the first death reinforces his pessimistic view, echoed as well in the presence of ‘Owl Eyes’ as the only person at Gatsby’s funeral. He singularly expresses compassion because he is one of the few who are not ‘blind’ to the truth. However, Dr. Eckleburg used as a metaphor of a faux God-like figure could also be a comment on the consequences of a hedonistic society existing in a state of confused moral chaos. His possibly empty eyes, symbolic of corrective vision, could epitomise the morally blind characters who fabricate reality, fantasise and misread each other and themselves whilst encouraging deceit and betrayal (endless misperception underlies the novel due to mistaken identities).

The causal factor could be absence of religion and absolute principles as the blank eyes of T.J. Eckleburg are not God but rather a long-dead oculist who should have been engaged in correcting vision instead of seeking commercial advantage by means of a gimmick which is itself an image of materialism[42]. This almost corrupted, ‘religious’ (according to Wilson) symbol dominates the ‘valley of the ashes’ which is itself reminiscent of the Psalmist’s ‘valley of the shadow of death’ [43] and a derelict version of a fertile rural landscape that reflects the ‘blind’ eyes of a society existing in a moral vacuum.

Equally, in the ‘Beautiful and Damned’ “the righteous of the land decorate railroads with billboards asserting in red and yellow that ‘Jesus Christ is God”, and place them ‘appropriately’ next to ‘Gunter’s Whiskey is Good’. This emphasises the barely contrasting messages, word plays on ‘God is Good’, which act as products of mankind’s will to assimilate power and materialism in place of what should be sacrosanct; religion is corrupt.

As ‘pioneers’ and ‘settlers’ in the contemporary world which has discarded the traditional ethics offered by religion and displaced them with the prevailing powers of wealth, it is not easy for Gatsby and Nick to achieve a corrective vision because they are drawn into an immoral world[44], blind to everyone who do not facilitate their own desire. The ‘blindness’ could be a result of religious deterioration; Fitzgerald asserts that ‘God’ may be dead, leading the lower men to anthropomorphise Him (projecting authority on a billboard), and meaning may be lost. However, this is not necessarily a moment of celebration.

Nevertheless, religion is often mocked by the characters, perhaps signifying an element of authorial intrusion by Fitzgerald. Richard ends ‘Tender is the Night’ as he “raised his right hand and with a papal cross he blessed the beach” on which his adulterous wife resided. He is perhaps similar to the ‘madman’ denoted in Nietzsche’s parable since the public’s “faces turned upward” and his religious sentiment is also solely worthy of mockery. His irrelevant habit of “suddenly unrolling a long scroll of contempt for some race, class, way of life, way of thinking” is criticised by the ‘higher’ Nicole as an influence of the moral absolutism Christianity asserts. Nicole’s ultimate realisation is that it is “better to be a sane crook than a mad puritan” and her renowned anti-realist perspective allows her to prosper and again taint religion as ‘mad’. Similarly, ‘blasphemy’ in ‘The Beautiful and Damned’ is not portrayed as contentious. Nietzsche’s own criticisms are reflected in Maury’s conviction “that everyone in America but a select thousand should be compelled to accept a very rigid system of morals” such as ‘Roman Catholicism’.

While the verb ‘should’ is dubious, he claims that the higher men who “adopt the pose of a moral freedom” are a clear minority, juxtaposing from the masses with little intelligence and plenty of ‘ignorance’. Anthony voices principles that seemingly adhere to logical positivism in his claim that dignified individuals “oughtn’t to accept anything unless it is decently demonstrable” despite consequential happiness and, therefore, “to believe was to limit”. Certainly, Richard’s criticism of the “apostles” distributing convictions of sin to control America’s youth proves to be “dangerous medicine for these ‘future leaders of men’” as the restrictions imposed will only minimise greatness.

He compares the concept of teaching religion to “frightening the amiable sheep” which is directly comparable to Nietzsche’s animalistic image of the ‘herd’. Moreover, religion is depicted almost as opium for fools in Maury’s satirical tale of the Bible’s creation: the original intent was to falsify humanity’s nonsense “so that it may last forever as a witness to our profound scepticism of our unusual irony” in creating an absurdly omnipotent deity whom should be a laughing stock. Ironically, Christianity was victim to literalist interpretations and usurped mankind’s greatness. Therefore, Fitzgerald reduces religion’s deontological morality to products of the herd’s irrationality as Nietzsche himself does.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Fitzgerald’s visions are arguably existential in nature and, if it is seen that he practices authorial intrusion in the language of his narration and the views expressed by the characters, the evidence provided is plentiful both in his novels and external interviews to conclude that he sought to abolish rigid moral norms reaffirmed by deep-rooted American tradition in a manner which can be traced to Nietzsche’s will to go ‘beyond good and evil’.

In fact, previous scholarly views have also invasively interpreted this argument, such as Berman’s ‘The Great Gatsby and Fitzgerald’s World of Ideas’[45] which notes differing aspects of the novel as influenced by Nietzschean thought [46] while Finklestein’s ‘Existentialism and Alienation in American Literature’[47] explicates the Nietzscheanism contained in Fitzgerald’s short story, ‘The Diamond as Big as the Ritz’. Fitzgerald’s own ‘Nietzscheanism’ is most potent in ‘The Beautiful and Damned’ with his humiliation of the ‘lower men’ and the pathetic morality of the ‘mediocre heretics’.

Nevertheless, some element of the presented moral failures in ‘The Great Gatsby’ does hold poignancy and regret in Nick’s mind as he ‘could not forgive’ the antagonistic Buchanans. Therefore, as Fitzgerald allows Nick to hold authorship of the book through a rejection of omniscient narration, there is some ethical crisis faced by both ‘authors’ through observing the degradation of social moral order, perhaps contrasting from Nietzsche’s idea of ‘the free spirits’.

Yet, this arguably coincides with Nietzsche’s intent which was, not to transform society into anarchy through demolition of all orderly standards, but rather to give the individual ‘higher man’ moral freedom. Nick’s imaginative excitement and ironic detachment hold imbalanced tension and express the two ways in which Fitzgerald perceives the world, emphasised through the narrative structure.[48]

On one hand, Nick is an aspiring Nietzschean and the other characters in his novels sometimes allude to the ‘higher’ man. But on the other, some form of ethical consciousness and compassion is required to avoid the chaos that ensues. Both the philosopher and writer agree that, in order to achieve excellence there should be a rejection of absolute moral principles originally deriving from religion and fear (including equality as presented in their mutual criticism of feminine ‘weakness’, rather than human women themselves).

This is often necessary to facilitate a singular defeat of the herd’s constraints and a possession of higher qualities. A Nietzschean perspective would label many of the character’s hedonism, dependency and idleness as weak and therefore their ‘immorality’ alone is unworthy of excellence, while Fitzgerald clearly holds some contempt for contemporary American society which disregards other people for the aforementioned reasons with little justification. Therefore, the portrayal of a lack of morality in Francis Scott Fitzgerald’s texts is not the main source for criticism according to either Fitzgerald or Nietzsche, although Fitzgerald admittedly deprecates it more greatly. It is society’s absorption with pleasure, disintegration and destruction which must be demolished whereas breaking moral laws should be encouraged to facilitate achievement, enterprise and greatness.

Bibliography

•Anon, (2016). [online] Available at: https://www.bu.edu/paideia/existenz/volumes/Vol.3-1Khazaee.html [Accessed 25 Feb. 2016].

•Berman, R. (1997). The great Gatsby and Fitzgerald’s world of ideas. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

•Brobjer, T. (2003). Nietzsche’s Affirmative Morality: An Ethics of Virtue. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, 26(1), pp.64-78.

•Cheshire, G, ‘Life and Times’, Fitzgerald, F. (2013). The beautiful and damned. London: HarperPress.

•Finkelstein, S. (1965). Existentialism and alienation in American literature. New York: International Publishers.

•Fitzgerald, F. and Turnbull, A. (1964). The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald. London: The Bodley Head.

•Fitzgerald, F., Bruccoli, M. and Baughman, J. (2004). Conversations with F. Scott Fitzgerald. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

•Helm, B. (2004). Combating Misogyny? Responses to Nietzsche by Turn-of-the-Century German Feminists. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, 27(1), pp.64-84.

•http://biblehub.com/psalms/23-4.htm

•http://www.dts.edu/read/an-interview-with-alister-mcgraith-mcgill-jenny/

•https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wHWbZmg2hzU, the school of life-philosophy-Nietzsche

•Leiter, B. (2004). Nietzsche’s Moral and Political Philosophy. [online] Plato.stanford.edu. Available at: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nietzsche-moral-political/ [Accessed 3 Feb. 2016].

•Nietzsche, F. and Collins, A. (1957). The use and abuse of history. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Educational Pub.

•Nietzsche, F. and Mencken, H. (2010). The Antichrist. [Waiheke Island]: Floating Press.

•Nietzsche, F., Kaufmann, W. and Nietzsche, F. (1967). On the genealogy of morals. New York: Vintage Books.

•Sanders, J’aimé L., “The art of existentialism: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer and the American existential tradition” (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2350

•Schacht, R. (2001). Nietzsche’s postmoralism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

•source- Knoll, M. and Stocker, B. (2014). Nietzsche as Political Philosopher. Berlin: De Gruyter.

•source -Nietzsche, F. and Kaufmann, W. (1974). The gay science. New York: Vintage Books.

•source: Fetterley, J. (1978). The resisting reader. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

•Theabsolute.net, (2016). Nietzsche – Writings on Women. [online] Available at: http://theabsolute.net/misogyny/nietzschewom.html [Accessed 29 Feb. 2016].

•Wininger, K. (1997). Nietzsche’s reclamation of philosophy. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

[1] Brobjer, T. (2003). Nietzsche’s Affirmative Morality: An Ethics of Virtue. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, 26(1), pp.64-78.

[2] Nietzsche, F. and Collins, A. (1957). The use and abuse of history. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Educational Pub.

[3] Leiter, B. (2004). Nietzsche’s Moral and Political Philosophy. [online] Plato.stanford.edu. Available at: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nietzsche-moral-political/ [Accessed 3 Feb. 2016].

[4]Cheshire, G, ‘Life and Times’, Fitzgerald, F. (2013). The beautiful and damned. London: HarperPress.

[5] Cheshire, G, ‘Life and Times’, Fitzgerald, F. (2013). The beautiful and damned. London: HarperPress.

[6] Cheshire, G, ‘Life and Times’, Fitzgerald, F. (2013). The beautiful and damned. London: HarperPress.

[7] Fitzgerald, F., Bruccoli, M. and Baughman, J. (2004). Conversations with F. Scott Fitzgerald. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

[8] Sanders, J’aimé L., “The art of existentialism: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer and the American existential tradition” (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2350

[9] Leiter, B. (2004). Nietzsche’s Moral and Political Philosophy. [online] Plato.stanford.edu. Available at: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nietzsche-moral-political/ [Accessed 3 Feb. 2016].

[10] Sanders, J’aimé L., “The art of existentialism: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer and the American existential

tradition” (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

[11] Fitzgerald, F., Bruccoli, M. and Baughman, J. (2004). Conversations with F. Scott Fitzgerald. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

[12] Anon, (2016). [online] Available at: https://www.bu.edu/paideia/existenz/volumes/Vol.3-1Khazaee.html [Accessed 25 Feb. 2016].

[13] Sanders, J’aimé L., “The art of existentialism: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer and the American existential tradition” (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2350

[14] Schacht, R. (2001). Nietzsche’s postmoralism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[15] Leiter, B. (2004). Nietzsche’s Moral and Political Philosophy. [online] Plato.stanford.edu. Available at: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nietzsche-moral-political/ [Accessed 3 Feb. 2016].

[16] Wininger, K. (1997). Nietzsche’s reclamation of philosophy. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

[17] Nietzsche, F. and Mencken, H. (2010). The Antichrist. [Waiheke Island]: Floating Press.

[18] Italics my own.

[19] seeking maximal pleasure for the majority produces moral actions as a desirable consequence- the rightness of an action depends entirely on the amount of pleasure it tends to produce and the amount of pain it tends to prevent

[20] source- Knoll, M. and Stocker, B. (2014). Nietzsche as Political Philosopher. Berlin: De Gruyter.

[21] Leiter, B. (2004). Nietzsche’s Moral and Political Philosophy. [online] Plato.stanford.edu. Available at: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nietzsche-moral-political/ [Accessed 3 Feb. 2016].

[22] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wHWbZmg2hzU, the school of life-philosophy-Nietzsche

[23] Leiter, B. (2004). Nietzsche’s Moral and Political Philosophy. [online] Plato.stanford.edu. Available at: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nietzsche-moral-political/ [Accessed 3 Feb. 2016].

[24] Can be compared to “But taken collectively, he (the American) is a mass product without common sense or guts or dignity” quoted from Fitzgerald in Bruccoli’s ‘Conversations’.

[25] Sanders, J’aimé L., “The art of existentialism: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer and the American existential tradition” (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2350

[26] Nietzsche, F., Kaufmann, W. and Nietzsche, F. (1967). On the genealogy of morals. New York: Vintage Books.

[27] Sanders, J’aimé L., “The art of existentialism: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer and the American existential tradition” (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2350

[28] Leiter, B. (2004). Nietzsche’s Moral and Political Philosophy. [online] Plato.stanford.edu. Available at: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/nietzsche-moral-political/ [Accessed 3 Feb. 2016].

[29] Fitzgerald, F. and Parkinson, K. (1987). The great Gatsby, critical study guide. New York: Penguin

[30] source: Fitzgerald, F. and Turnbull, A. (1964). The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald. London: The Bodley Head.

[31] source: Theabsolute.net, (2016). Nietzsche – Writings on Women. [online] Available at: http://theabsolute.net/misogyny/nietzschewom.html [Accessed 29 Feb. 2016].

[32] source: Helm, B. (2004). Combating Misogyny? Responses to Nietzsche by Turn-of-the-Century German Feminists. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, 27(1), pp.64-84.

[33] source: Fetterley, J. (1978). The resisting reader. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

[34] Fitzgerald, F. and Parkinson, K. (1987). The great Gatsby, critical study guide. New York: Penguin

[35] Theabsolute.net, (2016). Nietzsche – Writings on Women. [online] Available at: http://theabsolute.net/misogyny/nietzschewom.html [Accessed 29 Feb. 2016].

[36] Wininger, K. (1997). Nietzsche’s reclamation of philosophy. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

[37] Theabsolute.net, (2016). Nietzsche – Writings on Women. [online] Available at: http://theabsolute.net/misogyny/nietzschewom.html [Accessed 29 Feb. 2016].

[38] source: Helm, B. (2004). Combating Misogyny? Responses to Nietzsche by Turn-of-the-Century German Feminists. The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, 27(1), pp.64-84.

[39] source -Nietzsche, F. and Kaufmann, W. (1974). The gay science. New York: Vintage Books.

[40] http://www.dts.edu/read/an-interview-with-alister-mcgraith-mcgill-jenny/

[41] Sanders, J’aimé L., “The art of existentialism: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer and the American existential tradition” (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

[42] Fitzgerald, F. and Parkinson, K. (1987). The great Gatsby, critical study guide. New York: Penguin.

[43] http://biblehub.com/psalms/23-4.htm

[44] Fitzgerald, F. and Parkinson, K. (1987). The great Gatsby, critical study guide. New York: Penguin.

[45] Berman, R. (1997). The great Gatsby and Fitzgerald’s world of ideas. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

[46] Sanders, J’aimé L., “The art of existentialism: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer and the American existential tradition” (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations.

[47] Finkelstein, S. (1965). Existentialism and alienation in American literature. New York: International Publishers.

[48] Fitzgerald, F. and Parkinson, K. (1987). The great Gatsby, critical study guide. New York: Penguin

Leave a comment