*spoilers ahead*

The White Lotus, written and directed by Mike White, is a sharp social satire that follows the exploits of both hotel workers and their ultra rich guests at global resorts around the world. Touching on topics such as colonialism, class, race, wealth and gender dynamics, this captivating comedy drama covers the span of one transformative week for all the characters. With each passing day, darker themes start to emerge as diverging power dynamics are slowly explored, with tension building to a climax in the 6th episode. While the locations change (with season one based in Hawaii and season two in Sicily), one thing remains constant– the decline of both the travelers’ picture perfect facade and the hotel employees’ cheerful front.

Episode one of every season (so far) opens with the aftermath of a death, sharply contrasting from the idyllic setting we’re plunged into immediately after the opening score. The audience is teased into believing that this could be a ‘whodunnit’ mystery murder, perhaps something similar to Knives Out. Instead, what unfolds is a series of seemingly ‘ordinary’ conversations. Eventually, the plot strays into stranger territory as the characters interact and the compounding tension builds until we’re invested in everyone’s stories. The realism that grounds the show is never replaced, but simply tested by a series of coincidences.

Every character exhibits a performativity of some sorts, wearing a mask even around their closest people. While the audience may initially fall for the ‘normal’ act of these seemingly random, perhaps even ‘mundane’ characters (except Jennifer Coolidge’s portrayal of Tanya, of course), the first thing you notice is how interesting even their smallest interactions can be.

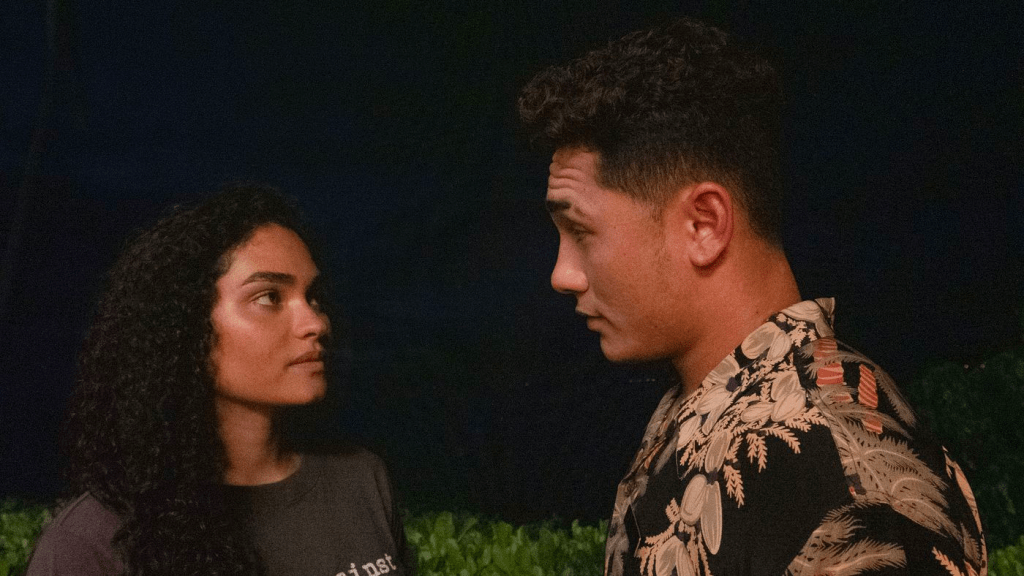

In season one, Olivia and Paula’s performative activism underpins their combined story arc. They’re shown reading The Portable Nietzsche and Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams on a chaise lounge by the pool, and at dinner they both correct Olivia’s ‘anti snowflake’ generation of parents (The Mossbachers) and chide their lack of political correctness. However, the entire time they continue enjoying the luxuries of a holiday resort that used to belong to the Native Hawaiians – this includes watching entertainment from those same people who make survive by working for their oppressors (the resort). While The White Lotus has been accused of being ignorant about Hawaiian culture in its portrayal of the Natives it tries to defend, there is nevertheless an interesting nuance explored in Paula and her romance with Kai, a Hawaiian worker at the hotel.

She begins by ‘empowering’ him to steal jewelry from the Mossbachers’ safe to gain ‘reparations’ for what happened to his tribe. However, when she realises that he may get caught, she doesn’t attempt to distract Olivia’s family and, while you’re made to believe that she can’t in that moment, the reality is that she made no attempts to prevent his discovery. In the end, she throws his bracelet into the ocean and forgets about him when she hears that he’s been caught. She reflects on his imprisonment, colonialism as a concept and all the sociological themes that she likes to engage in, but ultimately she remains implicit in the colonial structures that remain unmoved by the end of the season. While Paula is also a woman of colour, she is barely affected by Kai or his situation, befriending Olivia again and embracing the invisible umbrella of privilege afforded by the Mosserbachs. After all, she did go on vacation with the same rich, white family that she spends the whole time judging.

Similarly, Tanya tries to ‘buy’ Belinda’s (the spa worker’s) attention, time and emotional labour by weaponising the promise of investing in a business idea that she herself manufactures. By lifting Belinda’s hopes, she is able to keep her at her whim, only to crush them. Researcher Robb Rutledge composed a thesis suggesting that expecting too much of your future experiences, including vacations, may contribute to unhappiness. In this way, Tanya used money and power for a philanthropic pretense, only to create an expectation in Belinda that would actively make her unhappy in a job she already doesn’t love. At the end of season one, the gay and working class character of Armond ends up nothing but an ‘inconvenient’ dead body, with a tragic ending that goes unnoticed by the rich – even Shane, his ‘accidental’ murderer, is more annoyed by his domestic situation than the blood on his hands. Ultimately, every worker’s life is damaged permanently, while the guests remain virtually unaffected – to them, this is just another vacation. As Paula tells Olivia, “I guess it’s not stealing when you already think everything is yours”.

By touching on colonialism and patriarchy, The White Lotus reminds its audience that they’re also unextractable from these systems of oppression. Although we may feel some sense of satisfaction from critiquing and judging the characters, the meta-cinematic call to action is for us to realise that we can’t really separate ourselves from the power structures of wealth, gender, race or class. This is why, when characters like Olivia act as spokespeople for the world’s problems, it comes across as hollow and performative. We are asked to reflect on how even we ourselves are guilty of hypocrisy, as everybody kind of is, when we virtue signal about power structures that we’re not directly affected by (in the way that the workers are). That’s why it feels so empowering when, in season two, the workers do end up on top. The solution isn’t staying silent – we should keep discussing and wanting to improve, but we need to remember that we can only do so much and we’re not infallible. In a way, Mike White creates a unique kind of discourse around the current zeitgest and our obsession with discourse in general, which is usually thrown downwards from privileged people on a pedestal.

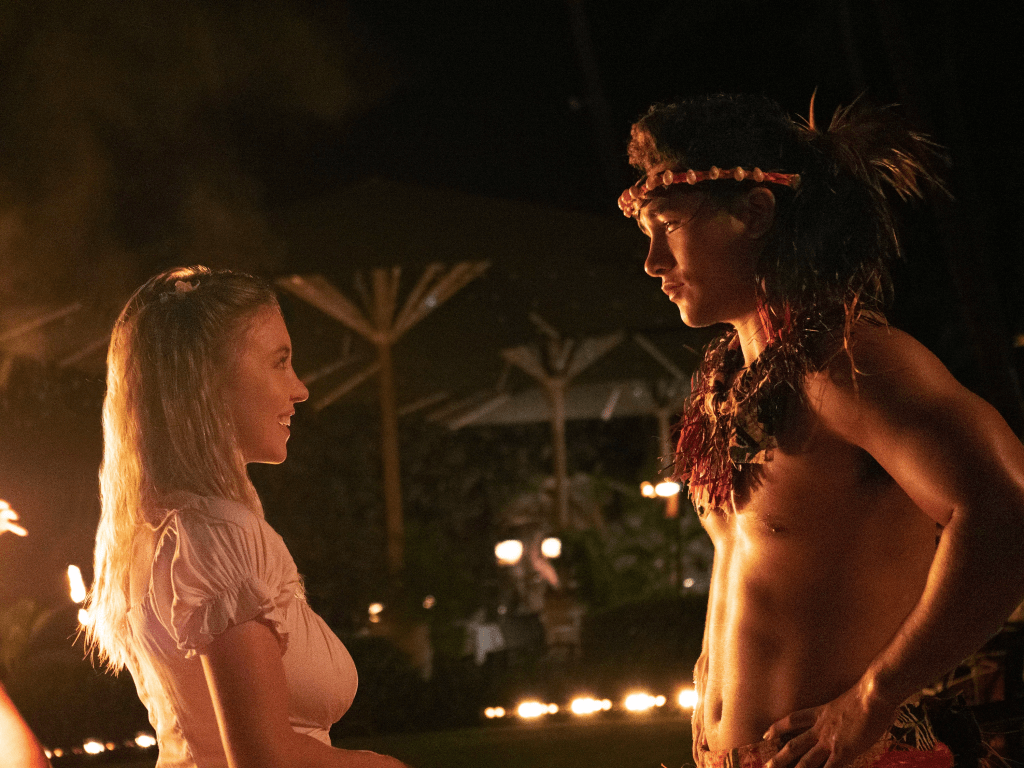

In contrast to the colonial subtext of Hawaii, where many of the staff are people of colour, in Sicily there isn’t the same character dynamic. Therefore, this focus on class warfare is redirected into an analysis of gender and sexual relationships, even when the ‘lower classes’ are entwined with the fates of upper class guests .

The characters in season two often act as foils to those from season one – Valentina and Armond are both closeted, gay resort managers who have an affair with an employee; Olivia and Paula are the less badass doubles of Luccia and Mia, who cosplay Thelma and Louise; the two couples and their difficult relationships hearken back to Rachel and Shane in season one with their marital dilemmas. Despite the change in scenery, it seems that everyone in The White Lotus still knows that their life is a sham, but are nevertheless desperate to appear a certain way. This is done through clothing (Portia, Tanya, Mia, Luccia), moral performativity (‘nice guy’ Alfie, Olivia and Paula), entitlement (Shane, Cameron, the Mossbachers) or social appearances (the couples). Even Quentin, the main antagonist of season two, displays an extravagant lifestyle to pretend he’s actually a wealthy aristocrat, when he’s actually in debt.

There are also parallels and intertextuality within each season. Alfie, who differentiates himself from the men in his family, ends up sleeping with Lucia and paying for it, just like his father. He still maintains that he’s different because he thinks he’s “in love”, but is actually in nothing but denial, wanting to fall for her fake story and feeling like he deserves a relationship with her because of this. He also feels entitled to be with Portia and, despite all the signs she isn’t interested, he still pursues her to her room while using the discourse around ‘toxic masculinity’ as a weapon of manipulation. At the end, all three generations of Di Grasso men turn to gaze at the same woman in the airport.

When Bert, the eldest, watches The Godfather, he sees the iconic quote: “Women in Sicily are more dangerous than shotguns”. This proves true for all the women in season two, particularly Daphne and Lucia, who both utilise their sex as power. Even Mia takes Guiseppe’s (the pianist’s) job by having sex with Valentina, despite actively not wanting to be a prostitute in episode one. Arguably, Dominic’s arc shows the most growth because he changes from being a cheating nymphomaniac to a better husband, father and person.

Tanya, the only character carried over between seasons, is the main driver of the plot in season two. Coolidge’s comedic timing coincides with the dramatism of the murder plot she finds herself in when she meets a group of aristocratic gay men who are plotting with her husband to murder her and take her money. They take her to see Madame Butterfly, an opera about a Japanese woman that falls mercilessly in love with a man who doesn’t return her feelings, leading to her suicide. This forebodes Tanya’s own tragic ending and echoes back to season one, where she says “the only thing I haven’t experienced in life yet is death”. She remains in denial, even when she sees her husband in a picture with Quentin, the leader of the group, or when he tells her another story of a rich woman being killed by a family who wanted to buy her island and she refused. Even Tanya’s final words demonstrate how out of touch she is with reality – “is Greg having an affair”, she asks the dying bodies on the yacht as blood spurts out of Quentin’s mouth. The queen of tragicomedy, Tanya herself dies from a mere fall after that harrowingly narrow escape. Yes, it was written in the cards, after all – hers was one of the dead bodies we hear of in the beginning.

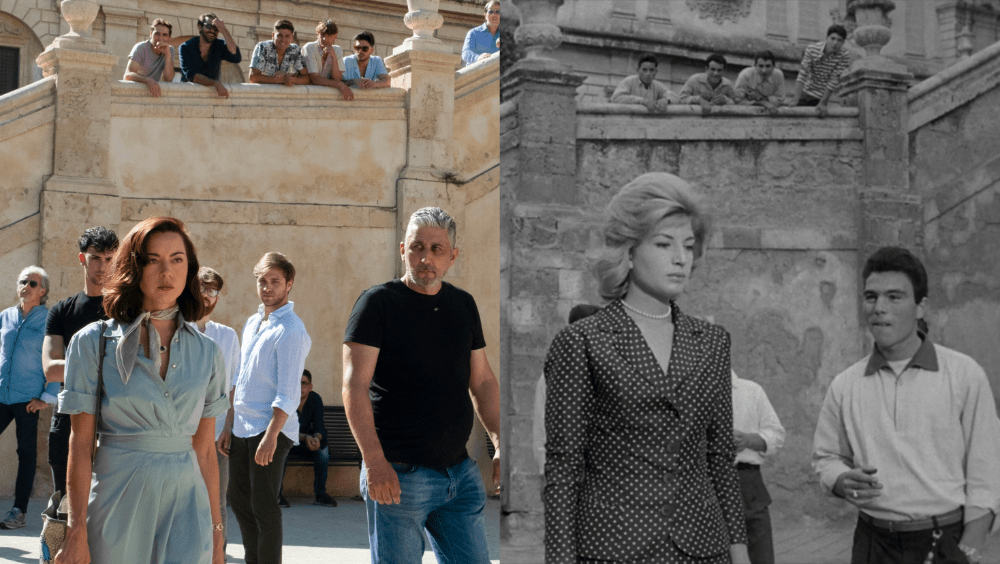

If there’s one thing The White Lotus does well, it’s satirising power and poking fun at it. White highlights the difference between fantasy and reality through Daphne and Cameron, who pretend they’re happy but consistently cheat on each other, and she even alludes to having kids with her trainer back in the city. Even Harper and Ethan, who pride themselves on being the ‘real’ and more intellectually compatible couple, end up with an empty relationship that needs infidelity to respark chemistry. Tanya and Harper are paralleled to Monica Vitti, but the former fails flagrantly when the ‘romantic’ Vespa ride isn’t the one she imagined. Not only do bugs fly into her mouth but her outfit ends up looking more “Peppa Pig” than La Ventura. Season two focuses on the discrepancies between fantasy and real life, which is especially prevalent in today’s culture of ‘romanticisation’. You can try to pretend but, in reality, humans are just going to be humans.

The 16th century art, featured in both the opening sequence of season two and through the Testa di Moro statues, is also rife with symbolism. The Testa di Moro are ceramic heads that tell the story of a woman who gave her virginity to a man that she was in love with. When he wanted to go home, back to his old country and his wife, she beheaded him. Ethan becomes obsessed with these statues, staring into them as the pain of infidelity, both Cameron’s and then Daphne’s, takes over his mind until the head shatters at the end, in the same way as his romantic illusions. Finally, he decides to cheat on Harper with Daphne to get revenge – which ironically does improve their relationship at the end of the show.

Throughout season two, the camera pans out to Mount Etna, using cinematography to convey the climbing tension as the volcanic eruptions call out to both themes of creation and death, which are tied to every storyline. The constant presence of the Ionian Sea provides an everlasting eeriness while what was supposed to be a paradisiacal holiday turns to hell. Season two’s scenery, symbolism, cast and location provide a unique layer to the already genius concept of season one. Every character is so nuanced and interesting that you can’t be disappointed when another plot enters the screen. It seems like The White Lotus keeps getting better, and we’ll be waiting impatiently for its season three return in 2025.

Leave a comment